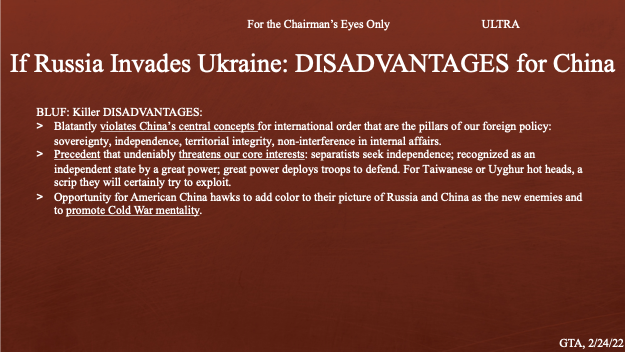

China must walk a tightrope between insisting on Russia’s legitimate security concerns and reaffirming its own commitment to sovereignty and territorial integrity.

Xi Jinping’s inner circle had a vigorous debate last week about the advantages and disadvantages for China of a Russian special operation in Ukraine. Their discussion included an assessment of the Biden Administration’s campaign to persuade Xi to use his influence with Vladimir Putin to get him to step back from an impending invasion. Many specifics about that campaign are reported by Edward Wong in The New York Times today. What is not reported, however, is that while asking for China’s help in his phone call with Chinese foreign minister Wang Yi, Secretary of State Antony Blinken also delivered a warning. If Putin went ahead with an invasion, unless China had made a serious, visible effort to stop it, Washington would indict China as a co-conspirator.

In a bit of diplomatic jujitsu, Blinken took a line from China’s talking points highlighting the dangers of a “new Cold War mentality.” As Blinken reportedly put it bluntly: if China were to give Putin a green light for a military invasion of a sovereign European country, it should expect to see a U.S.-Euro-Asian alignment against what might even be named a new Russo-Chinese “axis of evil.”

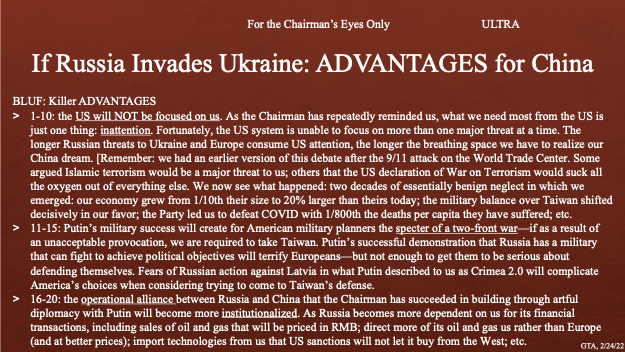

Xi has certainly analyzed China’s stakes in the current confrontation carefully. From what is known about his decisionmaking process, we can be sure that his strategic advisors have shown him at least two slides: one titled “advantages,” the second “disadvantages,” of a major Russian invasion. While we can wish we had access to those slides, in lieu of the real thing, this article offers one Western analyst’s draft of what they likely included.

Weighing the pros and cons, it is impossible to escape the uncertainties. How much impact will U.S.-led “crippling sanctions” have on global markets? How unified will the United States and Europe be when the costs of sanctions begin to bite—for example, if supplies of Russian gas delivered by the pipeline through Ukraine were interrupted? Could Western reactions to an invasion cause significant unanticipated disruptions that would rock other boats in China? Since no one can know the answers to these questions, it seems likely that Xi was conflicted.

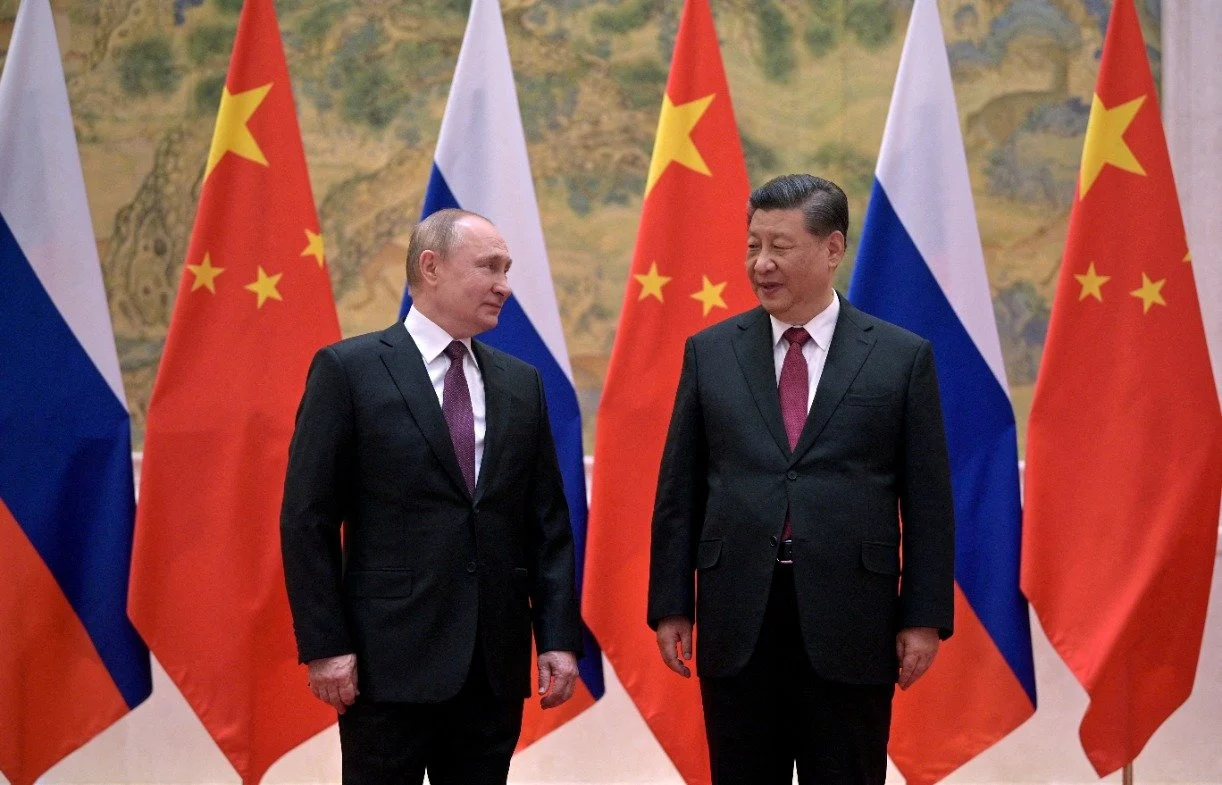

Nonetheless, if I were betting about what Xi said to Putin when they met in Beijing for a summit at the February 4 opening of the Winter Olympics (and repeated in their phone call today), his bottom lines were four. First, this is your initiative, not mine—and not one China would have chosen at this moment. Second, an invasion would create considerable discomfort for us—for all the reasons you appreciate. Third, nonetheless, we understand that you will do what you have to do. Fourth, if you go ahead, unless things go off the tracks, you can depend on China to have your back.

In sum: in the days and weeks ahead, will Xi’s China have Putin’s back? What will the Chinese government say? What will it do? Since this is playing out in real time, each of us can place our bets.

Whom will China blame for the crisis? Will it call Russia’s invasion an “invasion?” Will it recognize it as a violation of China’s principles of international order? Will it condemn Russia? And on the “do” front: will it vote for a United Nations Security Council resolution condemning Russia’s violation of the rules of the international order? Will it support U.S. efforts to isolate Russia from other international institutions or groups like the G20? Will it help Russian banks and companies ease the impact of sanctions?

My bet is that in both word and deed, China will support Russia. In allocating blame for causing what has happened, it will focus on the United States as the “culprit.” Of course, it will not endorse what is an unambiguous violation of China’s fundamental concepts and principles. But it will attempt to minimize damage to its own standing on these principles—walking a tightrope between insisting on Russia’s “legitimate security concerns” and reaffirming its own commitment to “sovereignty and territorial integrity.” It will call for the parties to negotiate and could even take a more active role in brokering an agreement in which Ukraine would accept a neutral status. But where it matters, when hard choices have to be made, China will have Russia’s back. And the analytic basis for my bet is my judgment that Xi has essentially defied geopolitical gravity in building a functional “alliance” between China and Russia that is operationally more significant than most of the formal alliances the United States has today.

Graham T. Allison is the Douglas Dillon Professor of Government at the Harvard Kennedy School. He is the former director of Harvard’s Belfer Center and the author of Destined for War: Can America and China Escape Thucydides’s Trap?