Guest Post by Eric Peters

A reader asks about comparisons being made between WuFlu and the 1918 Spanish Flu and specifically whether the precedent set then is legitimately applicable today.

He writes:

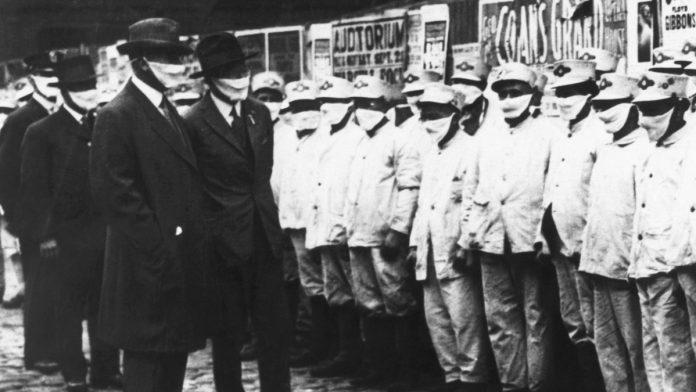

I am on a trivia email list that puts out a little “on this date” article each day and yesterday (March 4) marked the date in 1918 when the first “Spanish flu” cases were reported; so the article was facts about that pandemic.

It noted that in 1918 Americans social distanced, wore masks and schools and businesses were closed for months at a time, just like today. I see some issues with the comparison though; firstly that the demographic of the deaths and serious illnesses were quite different (Spanish flu affected young adults much more than WuFlu has) and also that medical care wasn’t nearly as equipped to treat symptoms a century ago as they are today and many deaths from the Spanish flu were due to misdiagnosis and improper treatment by doctors. I’ve noticed many in the media want to shoehorn WuFlu into the Spanish flu – “It’s 1918 all over again!” Do you believe there is a historical basis for such a comparison and what in your view would be a libertarian response to a pandemic the scale of the Spanish flu (if any different from the views toward WuFlu edicts)?

I think the main issue here isn’t who gets sick – or how sick or even how to treat the sick – but rather the same issue that’s the unspoken core issue of almost everything today since almost everything today has become an issue of the collective vs. the individual . . . which is really a false paradigm, once you dissect it a little.

Because there is no collective – other than as a rhetorical device.

When individuals form groups they do not become a “group.” They remain a number of individuals.

When individuals – most dangerously, politicians and other species of busybodies – speak in the collective, e.g., that “we” ought to be doing (or not doing) this or that “society” needs (or does not need) this or that, the speaker, who is an individual, means he (and the individuals who agree with him) hold that opinion and – usually – that he (and those who support him) intend to force – they never “ask,” despite their dishonest use of this otherwise noble word – everyone to do or not do whatever it is they are in favor of doing or not doing.

If any individual does not agree with “we,” then it is not “we” or “society” – that is to say, everyone – who is tacking this way or that way but rather some of “we” – i.e., the individuals who presume to speak for everyone – who are attempting to conflate their preferences with everyone’s preferences.

These individuals invariably fail to respect the right of the other individuals who disagree and who wish be left out of whatever it is that “we” intend to do – or insist be done.

Sometimes, the collective is a majority of individuals but majority status does not give the individuals who constitute it “supererogatory rights” above those properly belonging to individuals. If it is agreed that it is morally wrong for Joe to take Mike’s stuff then it cannot be morally right for Mike and Joe to take Bill’s stuff just because there are two of them and one of him.

On the same basis, Joe has the right to weigh risks – and assume the consequences of his decisions – with regard to his own health, which is properly (morally) no other individual’s business.

Just as people are (for now) free to take care of their health by choosing to eat sensibly and exercise, if they wish to do those things – and equally free to choose not to do those things – even if other people consider it salutary or “risky” to do/not do those things.

They also have the right to stay home or not; to open – or close – their businesses, as they deem appropriate. To wear a “mask,” if they think it prudent – just as many consider it prudent to exercise and eat sensibly.

Or not, if they so decide.

This idea that there is a collective health – and collective obligations as regards health – is morally obnoxious.

The fact that Joe is sick does not mean that Bill is sick – and Mike’s fear that Bill might be sick doesn’t give Mike the moral right to require that Bill pretend he is sick (and to wear a “mask”or “practice” various acts of kabuki) because Mike is fearful of the possibility that Bill might be sick.

The problem, of course, is that many individuals do think (or rather, believe) they have the right to impose their fears of might on other individuals. This has been the underlying but rarely articulated principle driving almost every political policy of the modern era – long before the WuFlu – because it has been embedded in the psyche of Americans for decades predating the WuFlu era.

For example:

It is has been asserted that driving faster than “x” MPH (even if it is only 1 MPH faster than “x”) might result in an accident and so driving even 1 MPH faster than “x” is forbidden by law and punishable, even when (as is almost always the case) there is no accident.

It is not necessary to establish that harm was caused. It is enough to assert that it might have been.

No matter how abstract the might.

It is asserted that a person who possesses a gun might use it to in a negligent or criminal way; therefore, possession guns by people who did not use a gun negligently or criminally is restricted or even forbidden; the person who ignores these restrictions and prohibitions is subject to criminal prosecution just the same as if he actually had used the gun in a negligent or criminal manner.

The injustice of this should be obvious.

Also the open-endedness that arises from the lack of clarity and specificity. Harm caused means something. It can be factually established – and factually rebutted.

You either did – or you did not.

Might can be literally anything. And inevitably, will be. The extremity of this standard is bound only by the willingness of people to tolerate the degree to which they are told they may not do this – or will be punished for doing that – based on what someone else worries might happen, if they do or don’t.

Acceptance of this standard many years ago by a large number of Americans is why healthy Americans are walking around wearing Face Burqas to prevent the transmission of a sickness they haven’t got and being coerced into submitting to a vaccination of unknown provenance and unknown risk, the consequences of that to be assumed entirely by them, as individuals.

They might be sick. They might spread sickness.

Anyone hypothetically capable of the act might also be a shagger of wee beasties, too.

Whether the individual actually has shagged a wee beastie is not relevant according to the terms of this collective, open-ended standard. Which is also a medieval one since not only is it based on the verdict of the mob, it is based upon the fears of the mob. Whipped up by demagogic individuals who pander to and exploit the fears of the individuals who are the mob.

There is no argument that counters fear because feelings are immune to reason. Burn the witch!

Wear a mask!

They embody the same standard.

Whether someone might be sick – or whatever else they might be – isn’t the issue. It is whether they actually are.

Unless, of course, we’re back in the witch-burning business – which appears to be exactly the “case.”

Guest Post by Eric Peters A reader asks about comparisons being made between WuFlu and the 1918 Spanish Flu and specifically whether the precedent set then is legitimately applicable today. He writes: I am on a trivia email list that puts out a little “on this date” article each day and yesterday (March 4) marked … Continue reading “Wu Flu vs. the Spanish Flu?”

Read More